In the fall, nature shows its glory as if with its last strength. This autumn has been exceptionally warm and sunny, and although the nights have begun to cool, the days in Southern Finland still feel almost like summer. Our bees are still buzzing actively around their hive, and the sun is so warm that I can comfortably write this post outside in our yard.

Despite the warm weather, the amount of light is diminishing rapidly and nature knows that. Trees, specifically, form their cycle mostly by the amount of the sunlight, not the temperature. The chlorophyll, or leaf green, retreats into the tree’s trunk. What remains in the leaves are the red and yellow pigments, known as carotenoids. This is why we start now seeing the vibrant shades of red and yellow around us. The glowing maples, the deep red color that ignites in rowan tree berries, the bright yellow aspens almost blinding in the autumn sun. In the fall we, too, often have a burst of energy before the season subsides. For many, fall feels like the beginning of the year, when school and new activities start.

Fall is also an active harvest time: a time to gather the fruits of the forest and garden, fill pantries with juices and jams, preserve mushrooms, and freeze berries. Little by little, the harvests fade, colors fade; turning to browns, turning to gray. The days shorten, nature settles down to rest. Trees and bushes shed their leaves, preparing for the long cold winter. Garden furniture is moved to the shed, water tanks are emptied, the woodshed is filled with firewood, summer cottage doors are latched closed. Winter approaches.

NAME:

Syyskuu (Finnish), meaning Fall Moon

September, or seventh month, from the Latin septem ‘seven’. The Roman lunar calendar began in March, so September was the seventh month in order.

Harvest Moon (Several North American Indigenous Peoples), Autumn Moon (Cree), Falling Leaves Moon (Ojibwe), Moon of Brown Leaves (Lakota), Yellow Leaf Moon (Assiniboine)

SPECIAL DAYS

– Syys-Matti 21.9.

– Fall Equinox and Celtic Mabon celebration on 22 or 23 September.

– Mielikki’s name day 23.9.

– Michaelmas 29.9.

Building the Fall-time Altar

Element: Earth

Colors: orange, yellow, brown, red, moss green, and gold

Aroma: apple, cinnamon, fallen leaves

Flowers and trees: colorful leaves, rowan branches, blueberry and lingonberry shrubs, heather, autumn hydrangeas, ivy, and cabbages

Stones: Spectrolite. Spectrolite is an unusual form of labradorite found in Finland, with a rainbow sheen from within its shimmering gray surface. It is believed to increase creativity and awaken a longing for beauty.

Other features: Because in fall we remember our ancestors and focus on cycles of nature, bones, teeth, and horns found in the forest can beautifully adorn an altar. All kinds of the fruits of the fall harvest are also suitable for the autumn altar, such as apples, rowan berries and, of course, pumpkins, turnips and other root vegetables — both whole and carved as jack o’lanterns.

Fall Equinox

In the Northern Hemisphere the Fall equinox falls about September 22 or 23. On the equinox, the sun crosses the celestial equator, moving from the northern half of the sky to the southern half, turning the northern hemisphere towards winter. The autumnal equinox can symbolize balance, because day and night are roughly the same length. In everyday life, we might focus on finding balance between, for example, work and rest, giving and receiving, or solitude and socializing. The point in the zodiac where the sun crosses to the south is called the first point of Libra, a sign of balance, harmony, and beauty.

Death, the cycle of life, and the celebration of the harvest are among the themes the fall equinox carries. The Celts celebrate the Mabon festival honoring the Green Man, the God of the forest and a symbol of the cycle of life. In Finland, we mark Mielikki’s name day, the mistress of the forest, on 23 September. The Fall equinox is an excellent time to thank nature and nature’s guardians for all the bounty we’ve had on our plates during summer and fall; everything we eat comes from nature.

A Fall Equinox Ritual: Thanking Mielikki, the Forest Goddess

Finns once asked help from the forest goddess, Mielikki, even more often than from the king of the forest, Tapio. Mielikki is the guardian spirit of small game, birds, trees, and other animals and plants, and was at the heart of many rituals. For example, an offering might be made when entering the forest on a hunting trip, to ask her to keep bears away. Part of the first harvest or catch of the season was offered to her at the foot of sacred trees to ensure good luck fishing and hunting. On your next forest walk, place a small gift of food or drink for Mielikki at the foot of your own sacred tree and thank the lady of the forest for the bountiful gifts in our kitchens and on our tables.

A Fall Equinox Ritual: Worshiping the Sacred Trees (– and it’s also the title of my next book!)

My first word was “puu”– tree in Finnish. When I was less than a year old, I sat in a baby carrier on my mother’s back and together we touched the rough bark of a pine. My mother said “puu”, and I soon repeated “phuu” after her. It’s said that we Finns are a nation of trees, and I identify with that deeply. We have always had sacred groves, inscribed initials of those who have passed away on trees, and believed in the magic that individual trees and their guardian spirits hold within. Traditionally, many houses had their own pitämyspuu — an offering tree. The first harvest, part of hunts, the blood of a slaughtered animal, or even the first drops of breast milk of a mother after birth were offered to the family’s tree. The sacrificial offering was intended to give thanks for harvest and hunting success, and ensure luck for coming years as well. The pitämyspuu might have grown for hundreds of years in the yard of the house and provided protection for the family over several generations. Tree worship was part of honoring both the dead and nature spirits. It was customary to give gifts to the tree during Feast of Saint Michael (29 September) and the Finnish and Karelian harvest festival, Kekri, to guarantee good luck.

My next book will be called Sacred Trees, and it will be published next year by SKS Kirjat, Finnish Literature Society. I have spent this week in their amazing archive in Helsinki, going through old story cards about trees. As recently as the 18th century, sacred groves still existed in Finland, but they disappeared quickly as the Church built its churches on the sites of these sacred groves, that used to be called hiisi in Finnish. However, an extensive collection gathered less than 100 years ago and stored in the SKS Archives reveals that tree worship was still a part of everyday life at the beginning of the last century – meaning that in my grandparents’ youth it was still commonly practiced! What also warms my heart is learning that tree worship was particularly active in Savonia—the region where my dear grandmother’s roots lie. Taking care of the pitämyspuut—trees dedicated to specific sacred purposes—symbolized respect for ancestors and the land, and ritualistic sacrifices were mostly done by women. I am deeply honored and grateful for the opportunity to revitalize these stories and bring them back to life for people today.

If trees were already important to our ancestors, they are also very important to us from the perspective of modern science. We know that forests are the lungs of the Earth: a single large tree produces enough oxygen for the needs of two people—more than 100 kilograms of oxygen per year. The role of trees in combating climate change and as carbon sinks is huge. According to recent research, trees have a significantly higher degree of consciousness than we previously understood. Trees communicate with each other, have relationships with their offspring and ancestors, and take care of each other even across species by sharing nutrients and warnings about dangerous insects, threats, or toxins. Even after death, trees continue their important role as maintainers of biodiversity. The trunk and root system of a dead tree often support thousands of microorganisms. As a building material, trees continue to play an important role in our lives: according to an Austrian study, wooden houses secrete an extract that promotes happiness and well-being.

Trees’ fall colors are like a final celebration of summer and life, before they give up their party clothes and hibernate, waiting for next spring. September is the perfect time to focus on the power of the trees before they fall silent. So get to know the traditional uses and magical powers of trees—and maybe you’ll find your own sacred tree too.

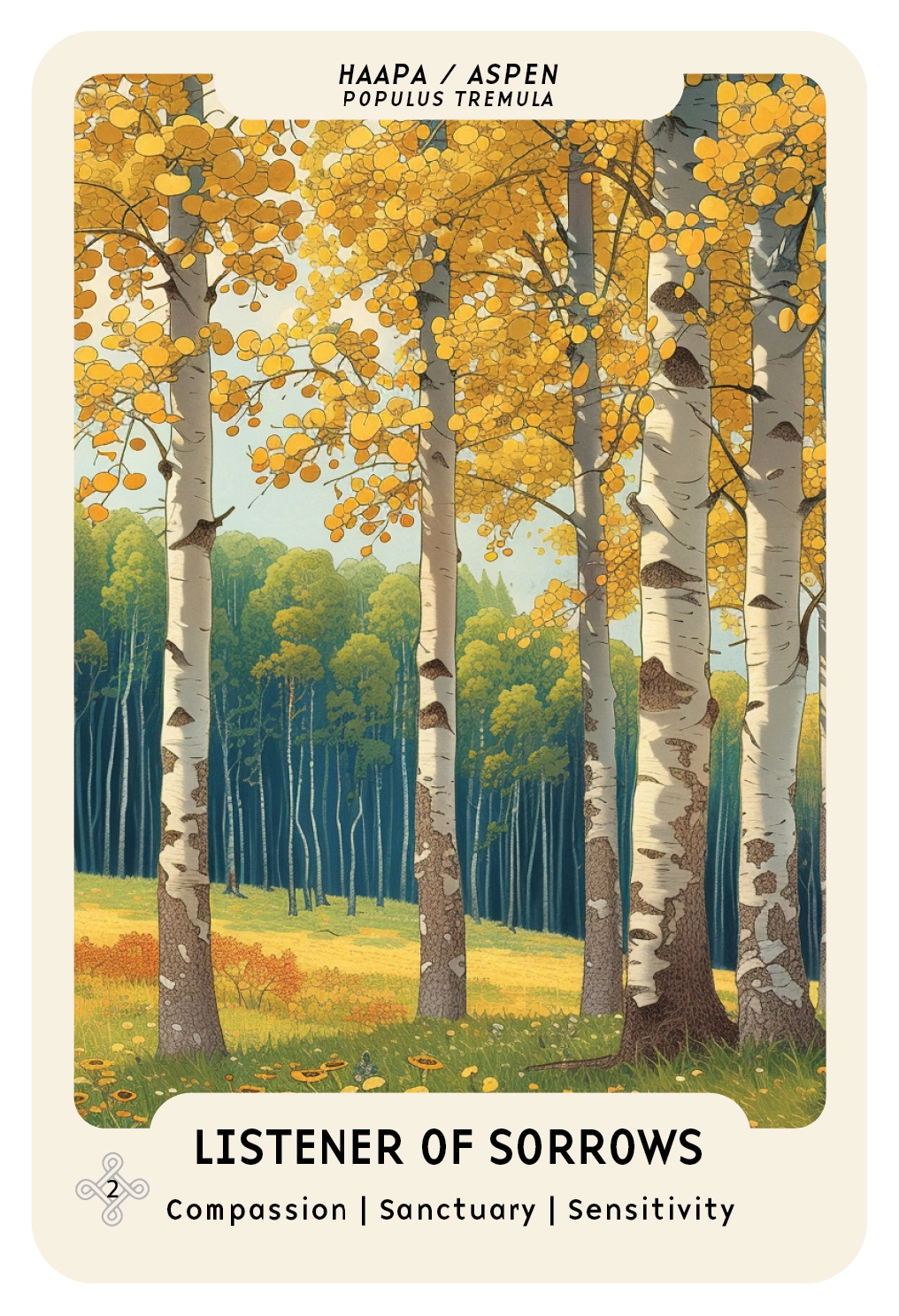

Haapa / Aspen – Populus tremula

The aspen is a sacred tree, hearer of sorrows, whose leaves dance in the wind in a unique way. The Finnish name of the tree, Haapa, is an ancient Finno-Ugric word and is related to haapio, a narrow boat carved from a single haapa. There were haapio already in the Stone Age, and the boat type is found among many indigenous peoples.

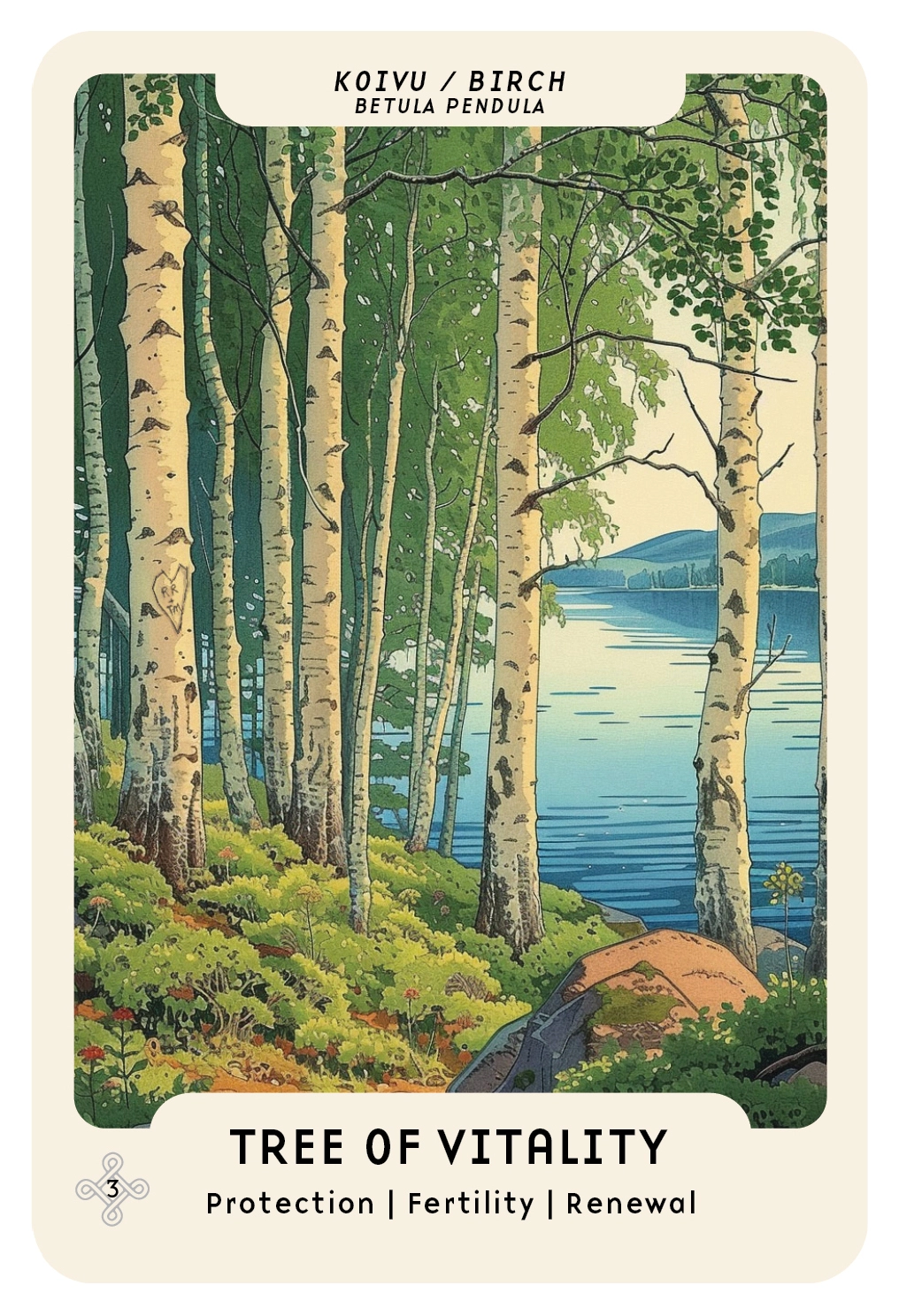

Koivu / Birch – Betula

Birch is considered a “world tree” among the Finno-Ugric peoples, and was an important offering tree for many households. It also plays a strong role in love magic and as a saunavihta, a small bundle of leafy birch branches used in traditional sauna-bathing for massage and stimulation of the skin. Rauduskoivu, silver birch, is Finland’s national tree.

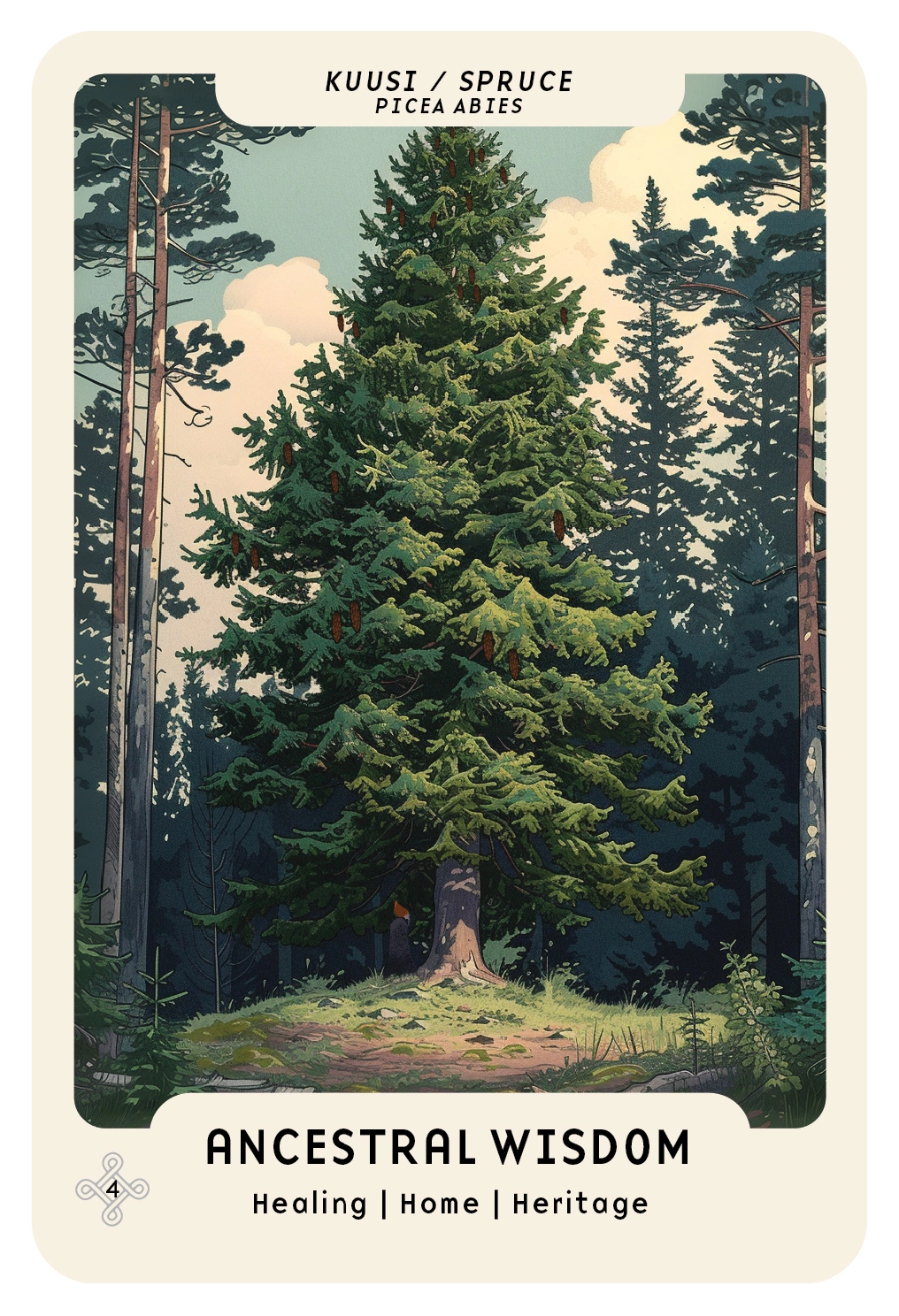

Kuusi / Spruce – Picea abies

Spruce was sacred to many healers and tietäjät (shamans or literally “knowers”). Spruce’s greenness in the middle of winter promised the return of life while nature was otherwise hibernating. The topless spruce that sometimes grow horizontally was considered Tapio, the forest god’s table, beneath which food and drink offerings were placed to ensure hunting luck. The spruce symbolizes home, ancestors, and family roots.

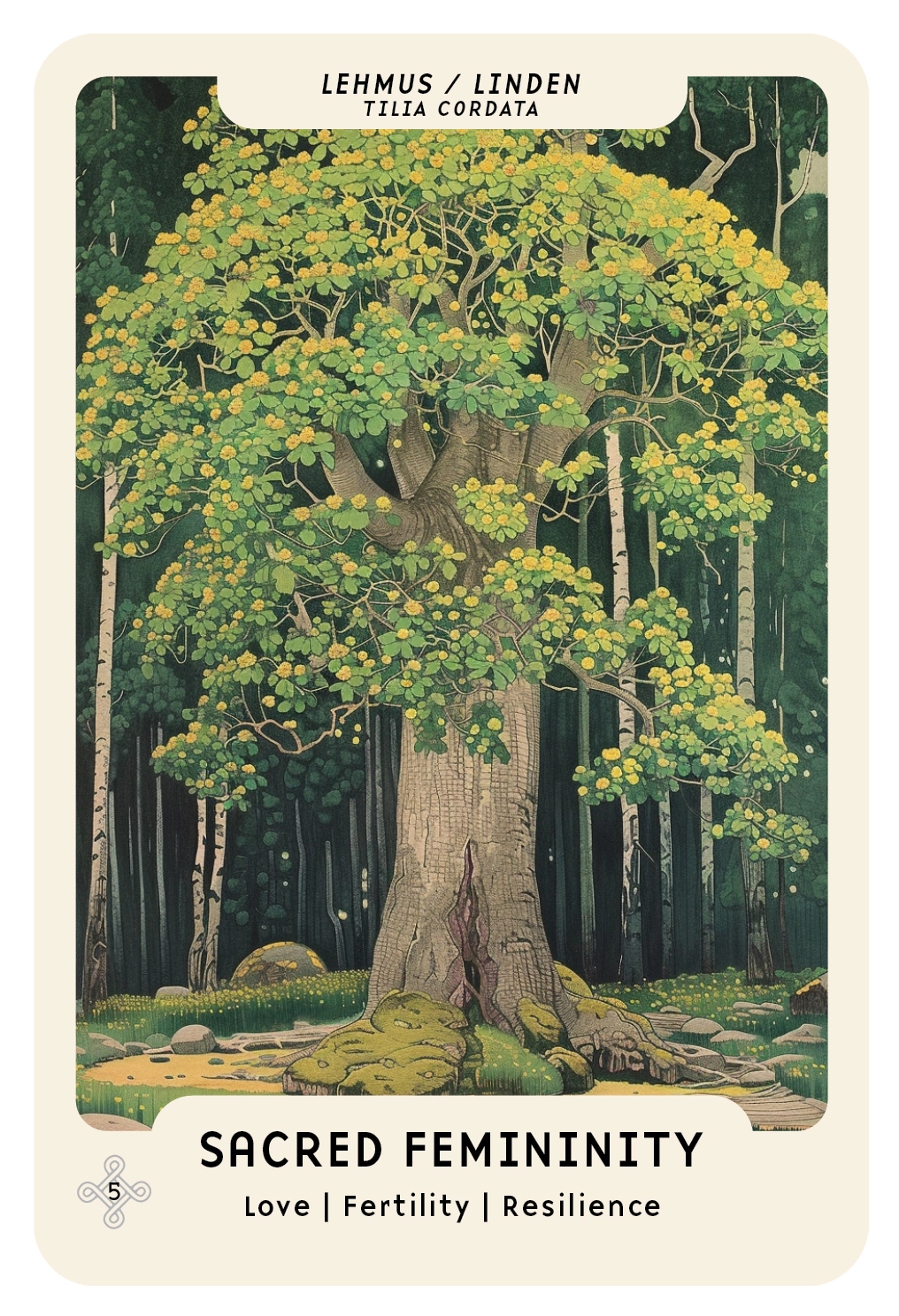

Lehmus / Linden – Tilia

Linden has been valued since the Stone Age: its fibers are used to make nets, ropes, and other braids. Linden was also considered a sacred tree and offerings were made to it. In ancient European tradition, lindens are associated with femininity.

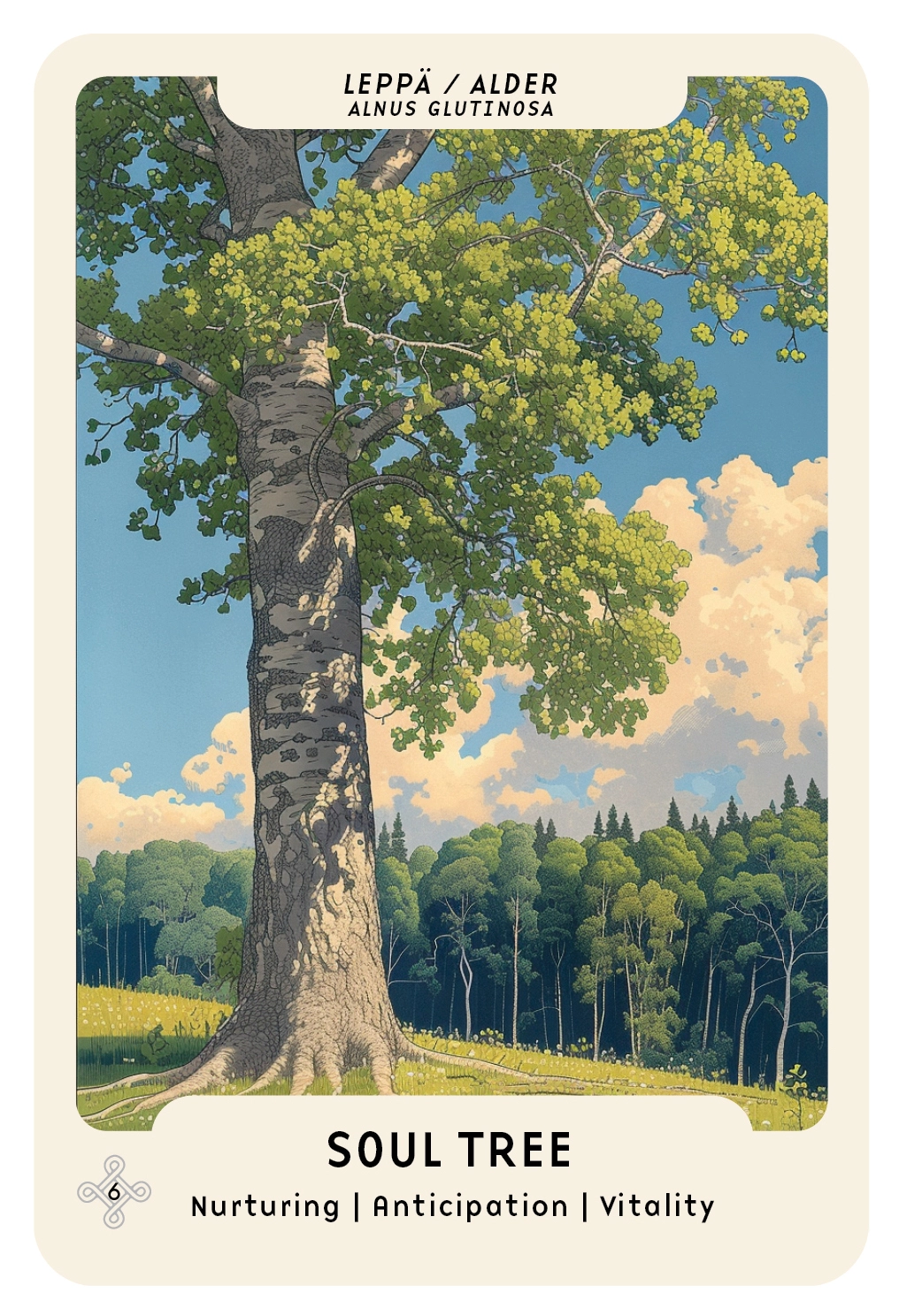

Leppä / Alder – Alnus

Alder’s red bark and the red liquid that oozes from the surface of a damaged alder symbolizes blood. Therefore the tree is often associated with women and fertility, and also called “the northern soul tree”. It gives its name to the ladybug leppäkerttu. Finland’s national insect, a mystical messenger that when it lands on you, you can send it off with a wish…

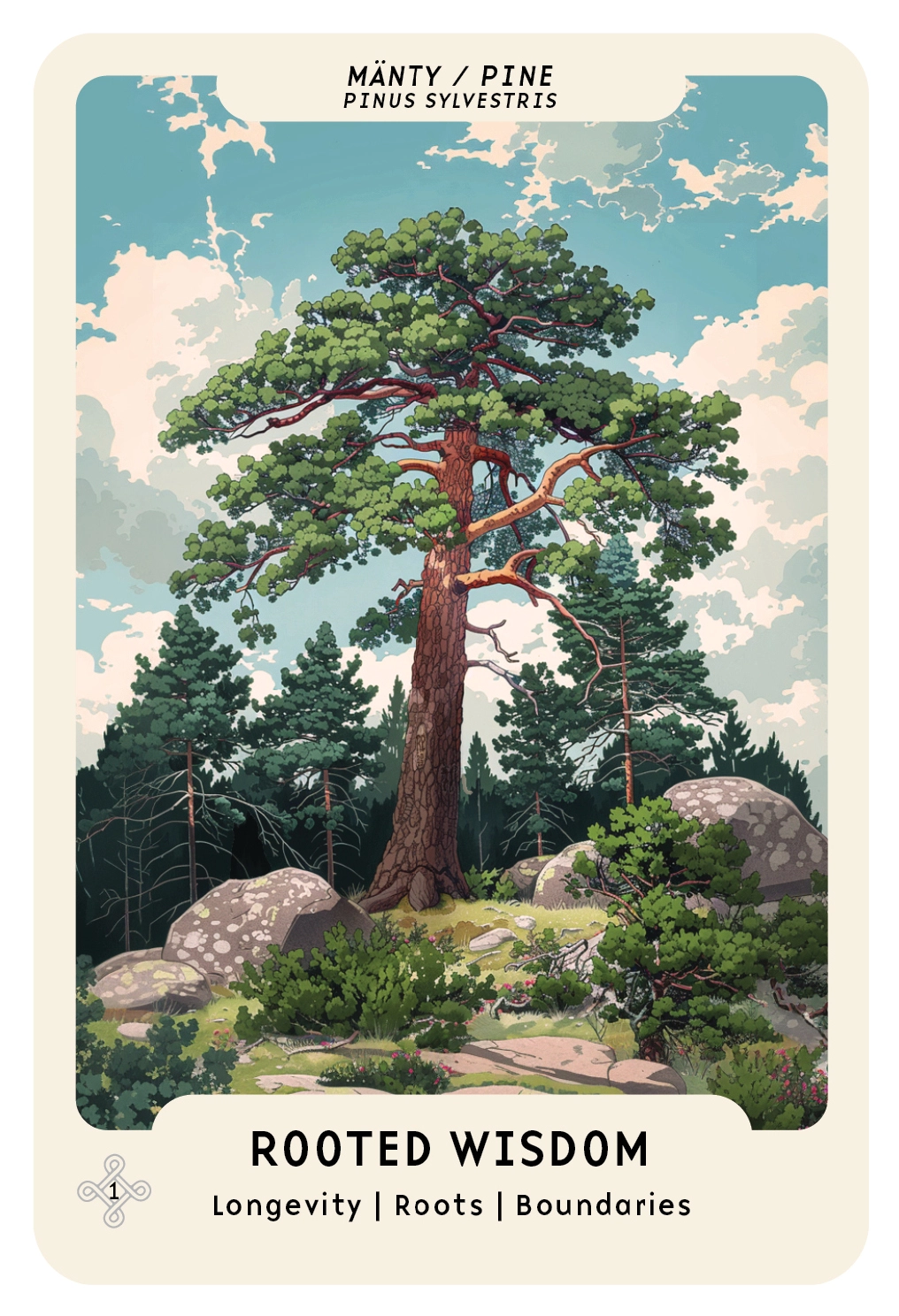

Mänty / Pine – Pinus sylvestris

The enormous pine trees have been the sacred trees of many families. Traditionally, after killing a bear, its skull was hung in the pine. From there, the bear’s soul was able to rise back to the heavens, onto the consolation, Otava’s (The Big Dipper’s) shoulders, where Finns believed the bear was born. Pines were also used as karsikkopuu, a tree where the initials of the dead were carved. It marked the border between the living and the dead, which the dead could not cross. Hongatar is the pine’s guardian spirit and protector of the bear.

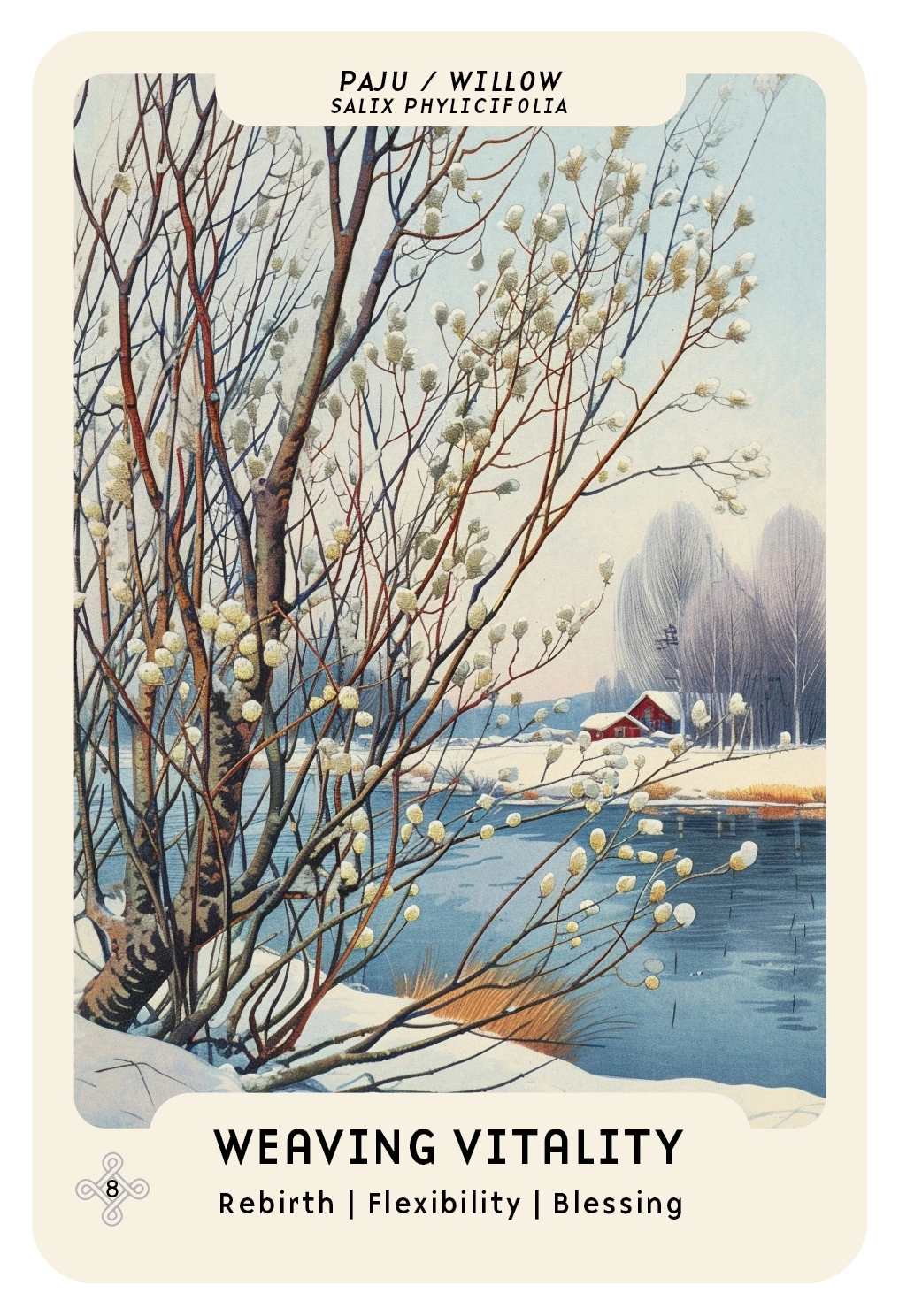

Paju / Willow – Salix

Willow is a tree of vitality. Willow branches are used by children for creating virpomisvarpu wands at Easter. It is among the first trees to bud after winter, and so is believed to have power as a conqueror of winter. Its pliable branches are woven into baskets and willow whistles, and nets are woven from its bark.

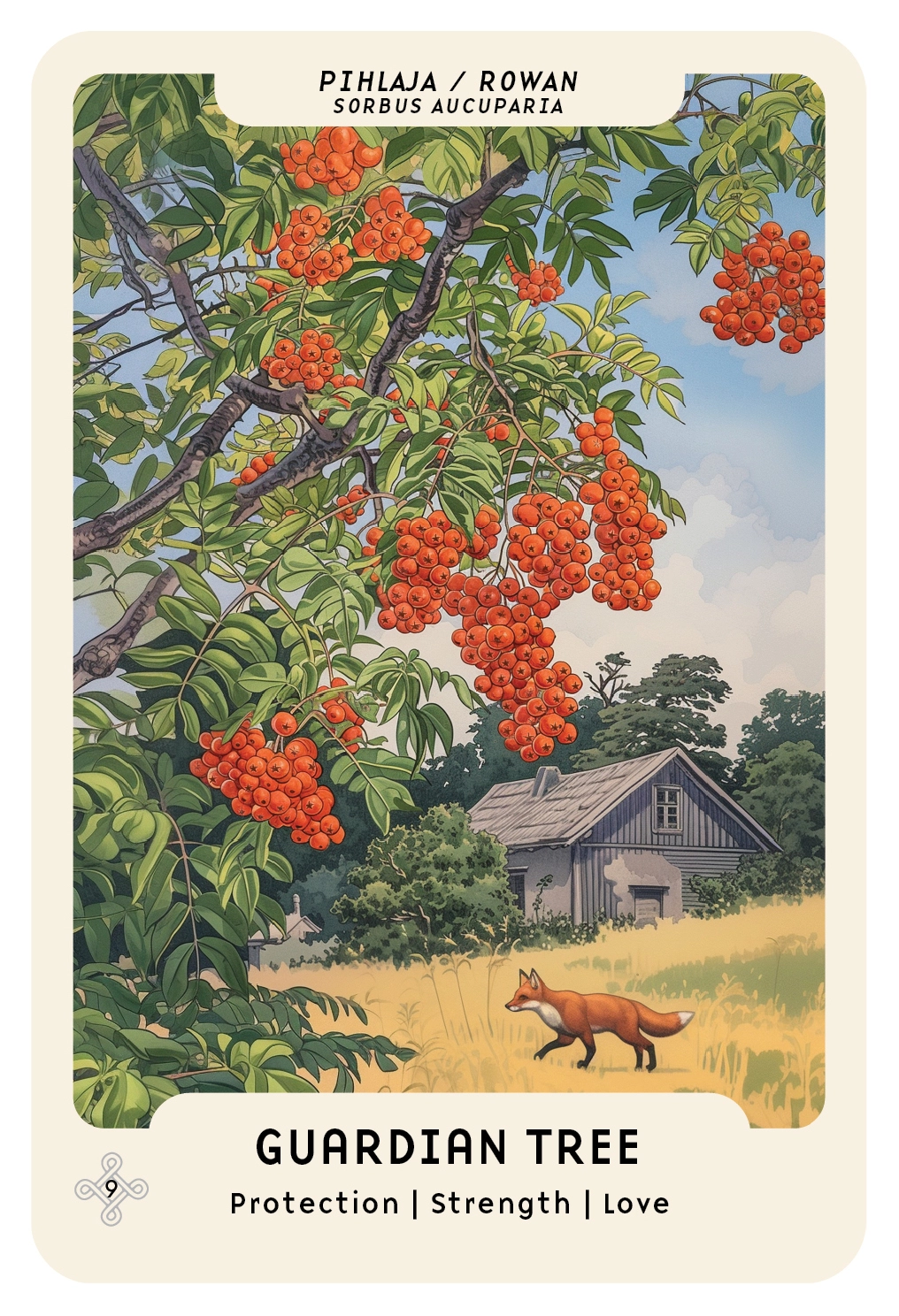

Pihlaja / Rowan – Sorbus

Rowan is a sacred tree, protector of women and children, and often the first to be planted in the yard of a new house to protect it from thunder. The rowan tree was sacred to Rauni, the god of thunder Ukko’s wife, so lightening wouldn’t strike a house growing sheltered by a rowan. The viiskanta, or pentagram, a five-pointed star on the end of the rowan berries, was associated with protection, love, and spells for protecting cows. When cows were allowed to graze freely in the spring, they were first made to pass beneath the rowan branches so they would receive protection from predators.

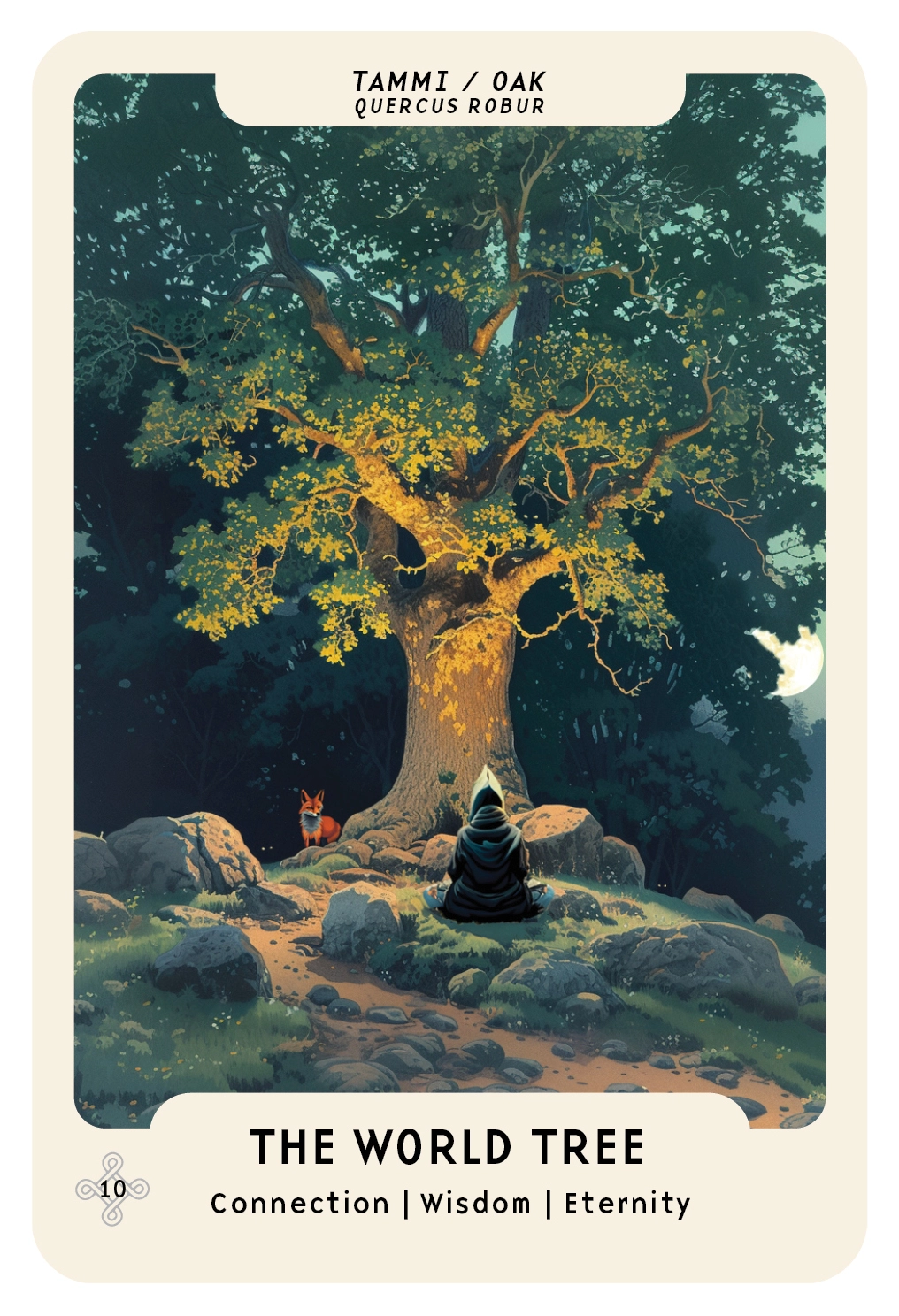

Tammi / Oak – Quercus robur

For the peoples of the north, the oak was the world tree, connecting the earth, the sky inhabited by the gods, and the world of the dead, or the underworld. For many peoples it was also the tree of the thunder god. Oak is a hardwood, called peasant’s iron, and is used for objects that require strength, such as barrels, furniture, and ships.

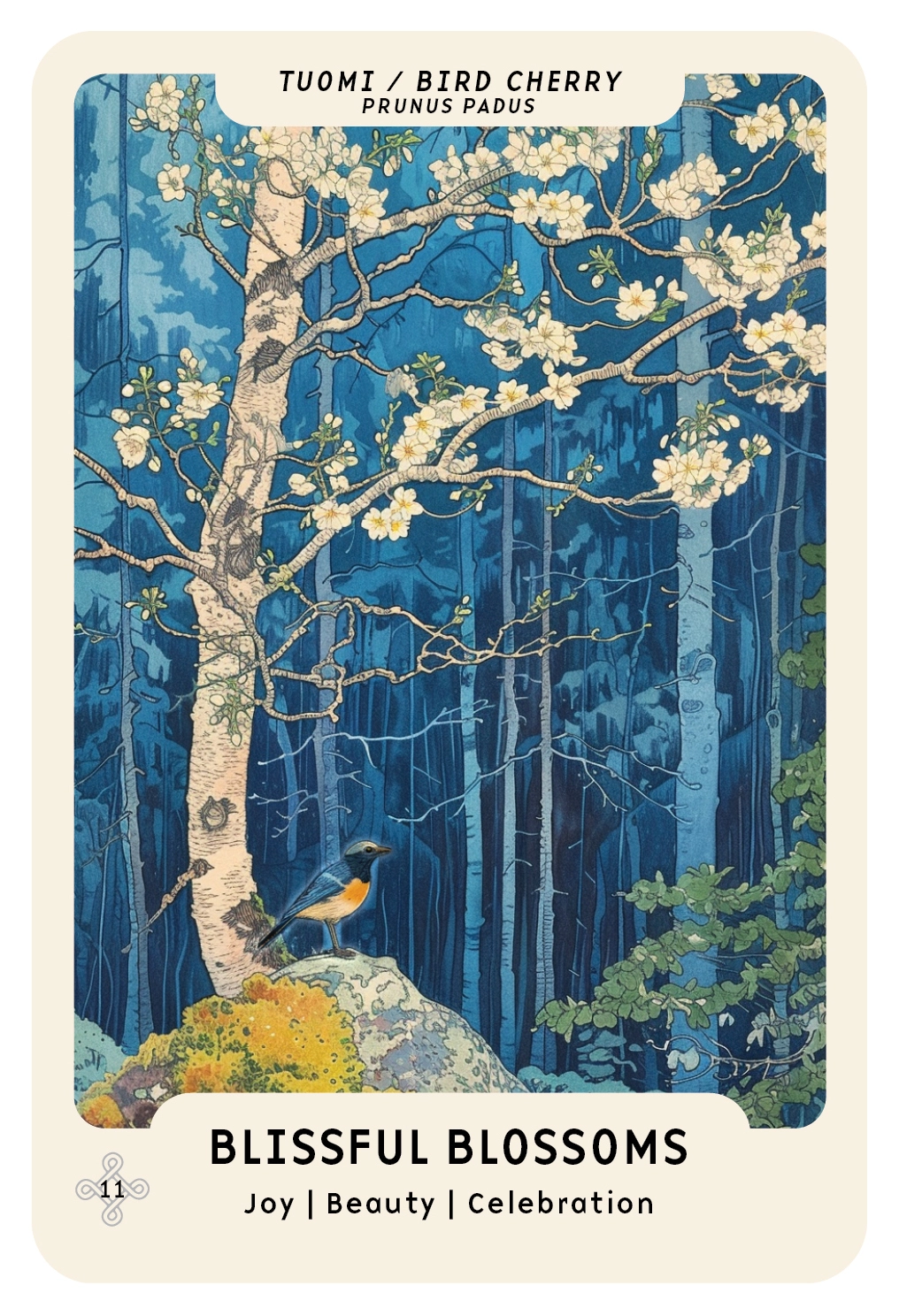

Tuomi / Cherry – Prunus padus

Cherry was the tree of joy and beauty, and haltia — the domestic spirits who protect household from harm. Its sour berries are made into flour for cakes, the flower’s scent is admired, and cherry branches used to craft various small objects.

Further reading

Ritva Kovalainen & Sanni Seppo: Tree People

Kåre Pihlström & Anneli Vihreä-Aarnio: Suomalaisten puut arjessa ja ajatuksissa [Finns’ Trees in Everyday Life and Thoughts]

The illustrations are from our magical Nordic Forest Rituals Oracle Cards which you can now also purchase as eBook only version.

September Ritual: Fall Mandala

The mandala is a sacred circular pattern used in many different cultures, often representing the inner or outer cosmos, reflecting our spiritual world or the universe around us. At its center lies the flower of life, symbolizing the creation and essence of the universe, surrounded by gates opening to each of the four cardinal directions. It serves as a tool for meditation and ritual, with its creation itself being a meditative process. Drawing, building, or simply observing a mandala is believed to promote relaxation, foster balance, and aid in contemplation and self-exploration.

The word “mandala” originates from Sanskrit, meaning sacred circle, center, or unity. Mandalas can be found throughout various cultures and religions. In the Christian tradition, they are represented by the rose windows of churches, while in Tibetan Buddhism, entire temples are constructed in the form of mandalas. Their patterns can also be seen in the sand paintings of Native American tribes. In Finnish homes, mandala-like patterns may appear in traditional “ryijy”, woven long-tufted wall tapestry or in oriental rugs.

Create your own autumn mandala using materials found in nature. You can place it on your altar indoors or outdoors, perhaps by the roots of your favorite tree, atop a high cliff, or in the sand of your backyard. Turn mandala-building into a ritual by inviting family members or friends to join. Crafting a mandala from natural elements is grounding, and admiring a beautiful fall mandala can be truly calming.

Would you like to learn more about rituals and live more in tune with the rhythms of nature? I share stories and insights about rituals now also in the form of a newsletter, approximately once a month. Join in!