Gray, dark, wet, and muddy. That’s how we Finns perceive October, especially if we have to recall the dark fall days around midsummer. Another name for the month has sometimes been likakuu, “Dirt Moon”. But our perception of October is quite wrong, as it is indeed a month of celebration!

NAMES:

Lokakuu (Finnish), formerly also likakuu, “Dirt Moon”

October, the eighth month, according to the Latin and Greek word ôctō. The Roman lunar calendar began in March, so October was the eighth month in order.

Drying Rice Moon (Dakota), Falling Leaves Moon (Anishinaabe), Freezing Moon (Ojibwe), Ice Moon (Haida), Migrating Moon (Cree)

SPECIAL DAYS

- Kekri from Michaelmas to All Saints’ Day

- World Animal Day 4.10.

- Day of Aleksis Kivi (Finnish writer) and Finnish Literature 10.10.

- First Winter Day 14.10.

- Halloween 31.10.

For the Romans, October was the eighth month, hence its English name October (Latin octō means “eight”). Native Americans aptly call October by descriptive names such as “Falling Leaves Moon,” “Freezing Moon,” or “Migrating Moon.”

In the Finnish traditional calendar, around October 14th, the branches bend downward, and winter begins. This also marked the start of a new yearly cycle, or at least the end of the old harvest year and the beginning of “kekri.” Kekri was the ancient Finnish end of the year celebration, followed by a period of jakoaika, division time, between the old and new years, during which the lunar and solar calendars were synchronized to stay in tune with nature’s cycles. But first, there was celebration! Kekri was the highlight of the ancient Finnish year, a feast marking the end of the exhausting harvest season and work year, followed by a couple of weeks of rest before the winter chores began. During kekri, sacrificial lambs were slaughtered, tables were set with abundance, beer was drunk, and festivities lasted for several days.

The cycle of the year and the associated worldview once connected many agricultural cultures around the world. Hence, the original Celtic Samhain, later Americanized as Halloween (All Hallows’ Eve), the Mexican Day of the Dead (Día de Muertos), and the Finnish Kekri share many similarities. The harvest year was coming to a close, and it was time to celebrate the cycle of life by eating, drinking, honoring the deceased, and in Finland, of course, by sauna. The time of Kekri was also suitable for performing spells. However, the most important thing seemed to be the celebration: it was believed that if there was no booze in Kekri, there was no bread in Christmas!

October Ritual: Kekri Celebration

The Kekri celebration does not have a precise date; instead, the festivities were held once the harvest had been completed. Nowadays, Kekri is typically observed between Michaelmas and All Saints’ Day. The celebration of Halloween began to spread to Finland in the late 1990s from the United States and other Western countries. Initially, the holiday was mainly celebrated among young people, but later it has gained ground more widely and is now part of Finnish autumn festive tradition.

As a counterbalance to this often-commercialized fest, kekri traditions have become increasingly prominent alongside Halloween. In our own Finnish-American family, we happily blend these traditions. We decorate the yard with carved pumpkin lanterns, enjoy a bountiful harvest meal, and have sauna with friends. We dress in spooky costumes and wander around the village in the twilight, trick-or-treating and collecting candies. Originally kekri lanterns were actually made from turnips in Finland: a turnip lantern, with a porous stick soaked in sheep’s fat burning inside, produced only a faint light and was therefore called kitupiikki, “pinchpenny.”

It’s delightful to gather seasonal delicacies grown in our own gardens or on nearby farms for the Kekri feast, potluck-style. Root vegetables, game, lamb, sausages, as well as berries, mushrooms, and cheeses have traditionally been served at Kekri celebrations. And, of course, self-brewed or locally brewed beer must not be forgotten; it is an essential part of the Kekri table.

The main thing is to have plenty of food and drink because during Kekri, one must eat abundantly, and if anyone goes hungry, it foretells a poor harvest year.

October Ritual: Kekri Night Sauna

Before, it was believed that the dead could visit their homes once a year without it being considered haunting. That day was the harvest festival Kekri. During that time, the border between life and death was fragile, and spirits were known to be active. On Kekri night, the sauna was also dedicated to the deceased: the living were not allowed in, but the sauna was heated for the spirits, who were also fed and given drink to ensure the household’s prosperity in the following harvest season.

So, remember to have sauna yourself earlier in the day on Kekri and skip the late-night sauna session. You can take a bowl of Kekri treats and drinks to the sauna for your deceased ancestors – this way, you ensure the happiness of your home for the next year as well.

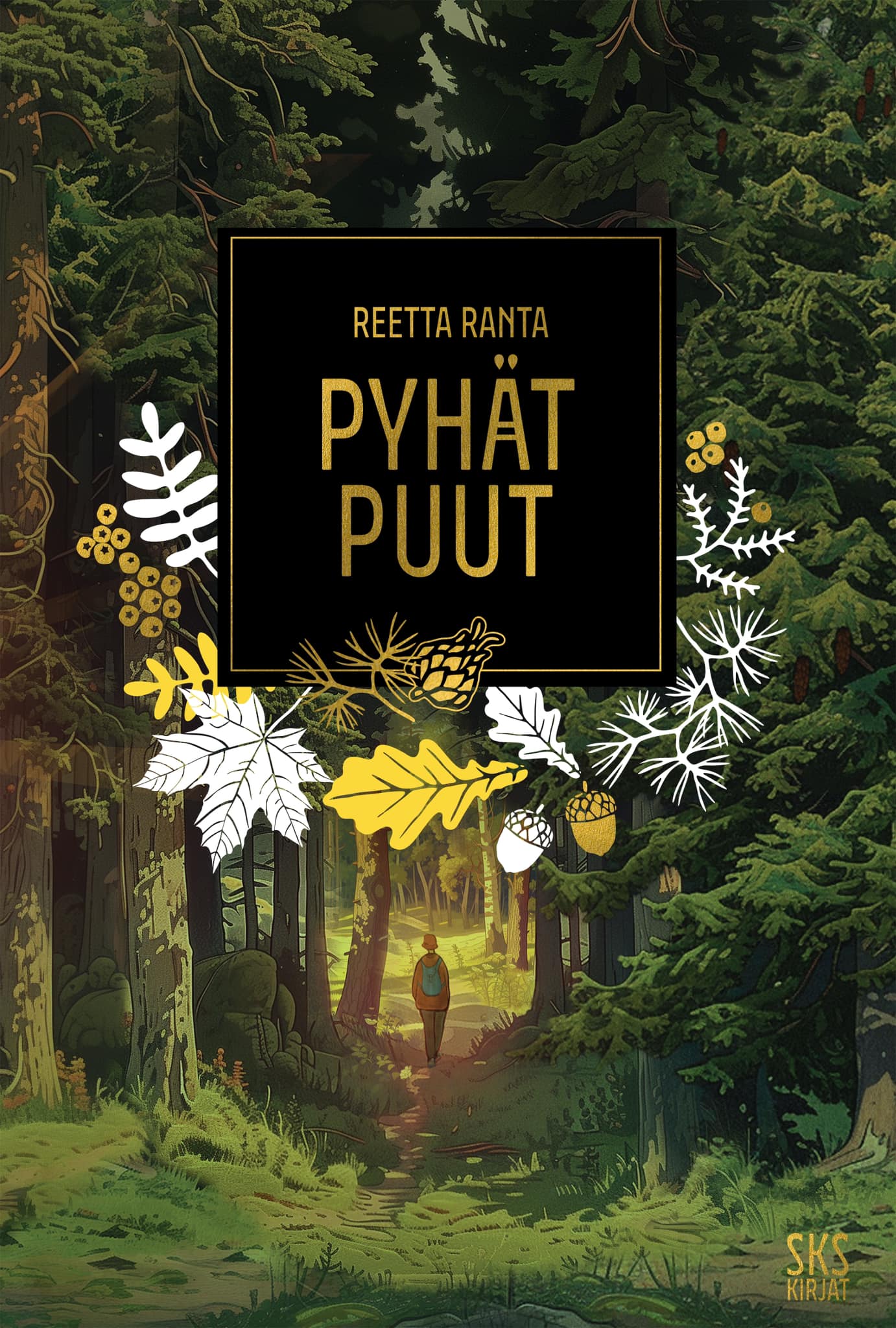

Coming soon: The Book of Sacred Trees

My first word was “puu”– tree in Finnish. When I was less than a year old, I sat in a baby carrier on my mother’s back and together we touched the rough bark of a pine. My mother said “puu”, and I soon repeated “phuu” after her. Nowadays, I live in the middle of the forest in Fiskars Village, in the shade of ancient pines and lush noble trees. It’s said that we Finns are a nation of trees, and I identify with that deeply. We have had sacred groves, inscribed initials of those who have passed away on trees, and believed in the magic that individual trees and their guardian spirits hold within. Trees were surrounded by stories, beliefs, and rituals that were an essential part of daily life and folk traditions.

As recently as the 18th century, sacred groves still existed in Finland, but they quickly disappeared as the church built its places of worship on the sites of these ancient sacred groves, known as hiisi. Contrary to popular belief, tree worship continued long after that: less than 100 years ago, many households still had their own pitämyspuu — an offering tree, a vital protector of the home and family. Offerings were made to these trees—grain, hunting catches, and even a mother’s first milk after childbirth. Women were often responsible for tending to these sacred trees, a practice known as lyylittely, which highlights the important role women played in these traditions and the matriarchal aspects of our belief system. The sacrificial offering was intended to give thanks for harvest and hunting success, and ensure luck for coming years as well. The sacred tree might have grown for hundreds of years in the yard of the house and provided protection for the family over several generations. Tree worship was part of honoring both the dead and nature spirits. It was customary to give gifts to the tree on the eve of major yearly festivals, for example during the Finnish and Karelian harvest festival, Kekri, to guarantee good luck.

The extensive archives of the Finnish Literature Society (SKS) contain hundreds of stories about offering trees and other sacred tree-related traditions and beliefs. I explored these stories while writing my upcoming book, Sacred Trees (SKS Kirjat, 2025). The research process opened up a whole new perspective on Finnish forest history and unearthed many forgotten tales. I can not wait to tell you more about it, so stay tuned 🙂